- Home

- Catherine McCallum

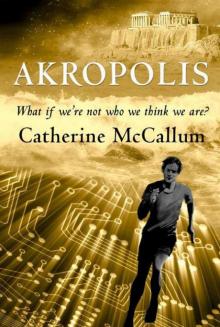

Akropolis

Akropolis Read online

AKROPOLIS

Catherine McCallum

Published by Catherine McCallum

ISBN 978-0-646-59321-0

Visit Catherine McCallum’s official website at

www.catherinemccallum.com

for the latest news, book details, and other information

Copyright © Catherine McCallum, 2013

e-book formatting by Guido Henkel

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Table of Contents

Prologue

Part 1: Lost at Sea

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part 2: The Long Walls

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part 3: America

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Epilogue

About the Author

Prologue

Remember, Norika, the story of my escape? As a small child you always wanted to hear it again, no matter how many times I told it. Now, as an old man facing my own death, I’ll tell it to you one last time.

I was thirteen when the earthquake struck. My father and I were eating our lunch in the Garden when our bowls started to move across the small table set under the oak tree, slowly at first and then with increasing speed, rattling together so the rice spilled to the ground.

My father’s employer had closed the Garden to the public that day. I wondered then if Kenji had known the earthquake was coming, he knew so much. When the ground started to rumble beneath us, Kenji ran from the temple courtyard and urged us to flee for our lives.

“Kenji-san, come with us! Don’t die here,” my father shouted above the noise of the falling city.

Kenji ignored his pleas. “Take your son and go. Find your wife and daughter.” Kenji always spoke in a manner to be obeyed. He turned and took the path towards the Zen garden.

“He wants to save Rock Island!” I said, starting off after him.

My father grabbed my arm. “No, Yoshiki, leave him!”

Together we fled through the gate as the earth heaved and opened. We ran with others running from their homes, past wrecked cars, around upturned carts with dead horses still in harness, through flying debris. The market was only a few minutes from the Garden but on that day we took longer to get there. Once, part of the road fell away in front of me and I started to slide into the chasm. My father, a slight man, gripped my arm with a strength I thought beyond him and hauled me to safety. “We’re nearly there,” he urged.

Near the market we heard our names called and I turned to see my mother and sister running towards us across the shifting road, still running as a toppling building crushed and buried them in a mountain of rubble and twisted metal. It happened so fast I remember only the shocked look on my mother’s face before she fell. The pile settled with a rumbling, grating sound, and then it all collapsed into the widening crack and they were gone. We both knew there was no chance they were alive. Dragging my father from the edge, I pleaded with him to leave.

We ran and ran. I turned only once to look back at the city, at my dead mother and sister, at our lost friends and neighbours. All I could hear was the thumping in my chest and I realised, even then, that it wasn’t fear or grief I felt but the exhilaration of survival. I knew I would never feel so alive again.

In this way my father and I escaped the catastrophe that destroyed our city. My mother and sister were among the thousands never found, the houses in our suburb were in ruins, and my life after the earthquake followed a different trajectory. We eventually arrived in Tasmania, and it was here where my son, your father, was born.

I used to think it was on that day, the day of the earthquake, I became a man. But it was on that day I became a survivor, like my forebears, and no longer just a Descendant.

Do you remember, Norika, how often you asked me to repeat the story? And how, each time, I found it hard to control my tears?

Part 1

Lost at Sea

1

Tasmania, 2020

Nat stood motionless, his phone poised to capture the right image. Too far away. The bird was about to fly. He moved closer to the edge of the cliff, his tall, spare frame light on the ground, the harsh coastline utterly familiar to him. He made no sound and left no tracks. Around this area of the coast, he and his brother were known for their tracking skills.

The sea eagle was perched on a dead tree in the scrub back from the rocks. Haliaeetus leucogaster. White-breasted with soft grey over the wings, smaller than a wedgetail but still a large bird, she was wary, watchful. She knew this boy, the birder, knew he’d been tracking her.

He stopped, waiting. Across the clear air he heard something, a quick movement, the crack of a stick. The sea eagle turned her head sharply. Nat lowered the phone and looked to the north. A figure stood on the headland a short distance away, close enough for Nat to catch the glint of a rifle held ready to fire.

He froze. A shooter.

He raised his hands to clap, wave, yell, do anything to cause the bird to take flight and escape, but held off. She’s not the target. With growing fear he reminded himself why he’d come to the cliff early that morning. His eyes followed the shooter’s line of sight to the beach below.

Seb stood on a rock platform, gazing out to sea.

Nat shouted, screamed across the distance, “Seb! Run!”

The sea eagle took startled flight. Seb turned, saw Nat and ran from the rock as the rifle fired. Nat watched as he made it to the scrub. Heart pounding, he scrambled down the cliff, ignoring the teatree and kunzia tearing at his bare legs, the cold sweat stinging his cuts. Still fearful, he ran along the rocky beach towards his brother.

Seb was waiting for him. “I told you not to follow me.”

Nat started to shiver, holding his arms tight to his body. “Are you crazy? I just saved your life! Some psycho’s trying to kill you. Why don’t you do something?”

“I’m dealing with it, okay?”

“What about last time? They weren’t accidents, he missed. You need to tell someone.”

“Not yet. It’s too soon.”

Nat felt his energy fast draining. He sank to the ground beside Seb. “What’s going on, Seb? What’s happening?”

Seb was scanning the cliffs for the shooter. “I think he’s gone. Let’s go.” He rose to leave.

Nat tried to block him. “You know who it is, don’t you? You know who’s tracking you.”

Seb hesitated. “I’ve been getting text messages.”

“Like what?” Nat was still.

“I don’t want you involved. Forget it.”

Nat stared at him. �

��Don’t go out to sea tomorrow. It’s not safe. There’s a storm coming.”

“I’m safer out there than anywhere. It’s our last season, Jake wants a good catch.”

“Rick will be on board. One deckhand’s enough.” Nat waited. “Seb?”

“I’m going out. You worry too much.” Seb brushed him aside and started up the cliff.

Nat turned and went behind him. Together they followed the road back to St Annes, not saying much. They arrived home at dusk and went upstairs to get cleaned up. Nat again urged his brother to report the incident, tell their parents, the police, anyone. Seb refused, and watching him later over dinner, Nat knew he wasn’t about to change his mind.

* * *

The following morning Seb left the house before dawn.

Nat woke and heard him go. He wanted to call out after his brother but instead he lay still. Seb was like their mother, he thought, neither of them burdened with the need to explain themselves to others. He sometimes forgot he and Seb had different fathers. Their mother Luisa rarely mentioned her first husband and all Nat knew about him was that he’d died overseas when Seb was a few months old. When his mother remarried and Nat was born, Nat’s father Paul continued to raise both boys as his own.

At seventeen, Nat considered himself more responsible. Seb spent too much time by himself, camping in the bush or down the coast, removed from what was going on around him. Nat used to wonder what he thought of out there. Eventually he gave up wondering. Seb wouldn’t have told him anyway.

He remembered Seb had said something about text messages. Were they the same as the ones Nat had received? There was other weird stuff. Nat had kept a record, and his notes were increasing in number.

Downstairs he made himself coffee while his parents spoke together in low, worried voices. When he left for school they were still seated at the table, the radio tuned to the local station for weather updates. Although the Cormorant was not due back until the following night, by now everyone in town knew the forecast.

Nat was in class when the storm came. He gazed out the window at the gathering clouds and the wind in the trees, absently tapping a riff on the desk, over and over.

He became aware the class was silent and looked up. Mr Newman was standing by his desk, clearly waiting for the answer to some obscure question.

“Sorry. What did you say?” Nat said.

“Mister D’Angelo, have you heard anything of today’s lesson? I’m sure we would all appreciate your comments on the subject.”

Nat leaned back in his seat. Mr Newman was taking a risk, targeting him. The teacher used sarcasm as sport, usually directing his remarks at anyone he was sure wouldn’t return them. Nat sighed audibly, keen for the lesson to end so he could get home. “Sorry, Mister Newman.” He emphasised the Mister just enough for effect.

A couple of students gave muffled laughs. Pete Wilson snorted and tried to cover it up by looking accusingly at the others.

Mr Newman ignored them and continued to stare at Nat, who noticed a pink spot forming on the teacher’s cheek. It was always just one cheek, Nat thought, the left one. Weirdo. He stared blankly back.

“Be careful, D’Angelo. Be careful of what the ancient Greeks called hubris. Since the word was mentioned in today’s lesson, can you remind the class what it means?”

Nat allowed himself the briefest of pauses. “Over-reaching arrogance or ambition. Like when Icarus flew too close to the sun and made the gods mad at him. Or when Oedipus fulfilled a prophecy to murder his father and sleep with his mother.” He paused again. “Would that be right? Sir.”

More muffled snorts.

The final bell went. The class sat waiting to be dismissed. Nat lifted his pack to the desk and gathered his books—insolence in the teacher’s class had lately become his risk of choice. The others watched in silence as he shut down his computer and stood.

The spot on Mr Newman’s cheek became more pronounced. “Your attitude is disappointing, D’Angelo. The lesson was in fact about the conflict between the individual and the state, about the roles of the compliant citizen and the rebel. We were discussing the city-state of ancient Athens. Do you ever wonder why that dusty corner of the earth gave us the foundations of Western civilisation? Why science and learning flourished there over such a small period of time?”

Nat frowned. Where was this going?

The teacher continued. “I imagine you believe in so-called free will?”

The class was growing restless. Nat shrugged. “Of course.”

“But people need to be ruled, to be controlled, told what to do. The trouble with Athens was their belief in the freedom of the individual.”

“Athens was a democracy,” said Nat, “they believed in government by the people.”

“Only when it suited them,” Mr Newman said. “There were many slaves in Athens, none of them citizens. They were controlled by others.”

Nat was cautious. “Others?”

“Those superior to them. Surely you agree that a select few are always more suited to rule than the majority, that an elite group in charge of things is preferable to universal free will?” The teacher had become aware the class was looking on in puzzled silence, and his words trailed off.

Nat waited. “No,” he answered. He slung his pack over his shoulder. “The bell’s gone. I have to get home.”

Mr Newman leaned closer and said in a low voice, “The Age of Akropolis is upon us, Nathaniel.”

Nat stared. He’s crazy.

Mr Newman straightened and turned to the class. “You can all go. We’ll continue this discussion tomorrow.”

As he headed for the door, Nat wondered where they found teachers like Mr Newman.

Pete followed him outside and looked at the sky. “Bad storm coming.”

Nat had kept walking and Pete had to run to catch up with him.

“What’s wrong?” Pete said.

“Seb’s out there with Jake and Rick.”

Pete looked at him in surprise. “Didn’t they know the forecast?”

“Seb left early. I didn’t see him.”

“Jake and Rick would’ve known.”

Nat stopped. “Pete. I don’t know why they went out. Jake’s the skipper, he makes the decisions. They went out, that’s all I know.” He turned the corner and speeded up.

Pete caught him again, panting. “Did you know Jake’s sick? Cancer. Dad told me.”

Nat slowed to a halt. “Seb’ll be cut up.” His phone buzzed and he checked it. “That’s the third time.”

“What?”

“Some weirdo’s sending me text messages. The Age of Akropolis is upon us. That’s what Newman said to me in class.”

“He probably sent it.”

“There’s no sender ID, nothing. Just white text on a black screen.”

“It’s some cult,” said Pete. He lowered his voice. “Newman’s into that sort of thing. Meets people, I see him.”

“Did it ever occur to you that you’re creepy? You sound like a spy.”

“I keep my eyes open.”

“I’ll remember that.”

Pete hesitated. “Rick meets them too.”

Nat shrugged. “It’s a free world.” He glanced at his timeband: 4.15.

A loud clap of thunder startled them. The wind increased and rain started to fall. They broke into a run.

When Nat entered the house and saw his mother he stopped, concerned. She had arrived home early from the library and was on the phone, pacing while she talked, running her hands nervously through her hair.

There had been no sign of the boat, no radio contact.

Nothing until the next morning, when the Cormorant was reported lost at sea.

2

The families of those missing had been waiting on the wharf through the day, rugged up against the southerly straight from Antarctica. As the last of the storm turned to biting sleet the scattered group of watchers drew closer, maintaining the vigil despite the fading light. None could be sure

when the boat would make it in.

Nat stood with his parents. He’d heard the talk along the wharf, knew there would be an inquiry. Even if they came in safe, questions would be asked. Why had the Cormorant ignored the severe weather warning? Why had it gone out on a day when most of the fleet had remained in harbour?

In the way of fishing ports St Annes waited for news, suspending all doubts until the boat was found. The missing crew were locals, the town’s own. Jake Eastman was an experienced skipper, Seb and Rick were skilled deckhands. They were a crew well equipped to handle a storm at sea, even the worst, but the town knew it wouldn’t take much longer to accept they were gone.

Reports of the Cormorant’s location came through late afternoon from the last of the search helicopters. Before the crayboat reached harbour the group was informed one of the crew was lost at sea, no names confirmed. It was only later, after the Sea Rescue craft went out and guided the damaged Cormorant into port, when Nat and his parents saw Seb attaching the lines as Jake docked—it was only then they knew he was safe.

Nat’s mother had let out a small cry, a raw involuntary sound, when she saw him. Nat watched as his father held her, his own relief at his brother’s rescue replaced with a quick anger. He watched as Seb stepped up to the wharf and took his mother in his arms. The two clung together silently, without tears, alike in their restraint.

Nat walked away—not far, a few paces, enough—and forced himself to take two or three deep breaths, turning to greet Seb only when the cold, painful air had cleared his head.

He hugged his brother briefly. “Hey Seb.”

Seb spoke in a low voice. “I’m okay. Don’t worry.”

“Yeah, right.” Nat took a quick glance to make sure no one could overhear. “It could have been you who drowned out there instead of Rick. What happened?”

“I’m not sure. It’s not what you think. Keep it quiet.” Seb turned back to his parents.

Jake was standing next to Nat, looking pale and drawn.

Akropolis

Akropolis